Last June I applied for a Research Support Award (RSA). It was granted and the only condition attached was to contribute a piece to this blog. In my three years at Manchester Met I’ve received an average of one grant a year (each one for £500). The first was for an advanced oral history training course. The second was for travel, enabling me to visit case study sites. But I’ve never been asked to contribute to the blog. Without tempting fate, I’ve always been successful at getting these grants. So, if you haven’t tried – do!

“Ok, ok, but what was it for?” I hear you ask.

I am a landscape architect, and the subject of my PhD is Mark Turnbull, a Scottish landscape architect who recently died in 2016. It is a historiography, and I am drawing from multiple data sources including oral histories, but principally using his archive as a lens through which to view the land use planning tools and methods that Turnbull and his contemporaries pioneered during the 1970s, 80s and 90s.

I did not choose this topic, it came pre-packaged, and I applied for it like a job. Obviously, I had to make it my own, but it meant I had to get to grips with his archive from scratch. I had met Mark Turnbull (once), but I knew next to nothing about him, having spent most of my career practicing in the southeast of England. Fortunately, I was given privileged access to the archive before it moved to its final resting place at Historic Environment Scotland’s (HES) archive in Edinburgh this summer. Which, given the Covid 19 crisis that began unfolding 6 months into my PhD was a blessing.

However, my initial reaction to the archive was disappointment. Where was the drawing cabinet full of plans and sketches? It was not what I’d anticipated at all. No, this was a collection of reports – student and professional ones, by Turnbull and others; lectures, from his student days, and two A4 files of almost indecipherable notes for lectures that he had given; AND slides … case upon case of slides, plus two filing cabinet draws full of slide sheets. The latter were easy to handle on a light box, but the slides in cases, numbering eighteen in total, were jam packed and very difficult to extricate. Any the image was tiny on a light box – no detail at all.

At first, I ignored them. They could be the subject of a PhD for someone else, I told myself. And when Covid struck, and people suddenly had time, I majored on oral histories, frantically interviewing Turnbull’s fellow professionals, colleagues and ex-employees from the comfort of my own home – thanks to everybody’s new best friend, Zoom. Slowly the interviews activated the archive and it started to become alive.

Eventually, I realised I had to confront the slide collection. Turnbull originally trained as an architect at Edinburgh College of Art. In discussion with one of his old friends and fellow student, I started to understand the slide collection as Turnbull’s reference library. It was a key tool in an architect’s box of tricks – something he would have been encouraged to compile as a student. And of the few slides I’d seen, I knew that Mark had a good eye for photography. The collection was simply too big to ignore … in some ways it WAS the archive. Given some of the slides were labelled and dated, I was able to draw on their materiality and add substance to Turnbull’s timeline – to clear up discrepancies in dates at the very least.

By the time I got round to this, it was time for the archive to move. This meant I would have no access to it for several months. I quickly made a list of all the ones I thought worth scanning and started talking to HES about permissions and cost. They said yes, but it would cost approximately £25 per scan! I was furious with myself for not organising this sooner – surely, I could have found somewhere cheaper if I’d organised it myself? But I hadn’t. And this is when my supervisor suggested I approach MMU for another grant. As I said, I was successful, but given the cost of each slide, I would only be able to have twenty scanned. I had labelled about 400!

I set up a visit to the archive to select the chosen few. As the day approached, I received an email from a member of staff who said she might have found an alternative solution to my problem, but she couldn’t promise. I tried not to raise my hopes.

But low and behold, on my arrival, they had managed to set up a microfiche scanner that allowed me to scan the slides myself. They were not high-quality, but it meant that I could really get to grips with the slide library because I could view them at a magnified scale and keep a copy for my records. I am hoping to use some in my final thesis.

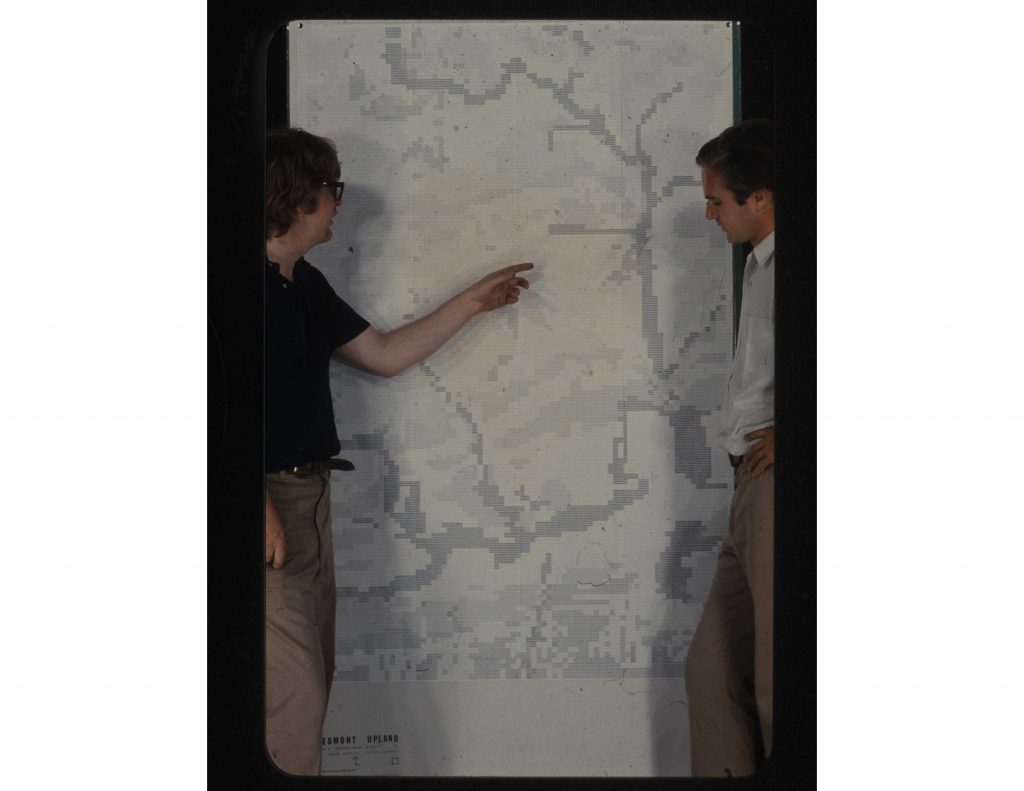

The library opening hours were 10am-4pm and the first day, I only managed to scan about half of the slides in one slide case – partly because I was trying to avoid peak rail fare rates. It was going to be slow progress, but this single slide proves that it was worth it.

I had already seen an A4 version of the drawing in this slide. However, this slide revealed the drawing to be enormous – without it I would simply have had no idea. And the drawing was key – the first visual evidence of Turnbull’s work to develop computer applications for manual land use planning methods – I have since discovered others.

To top it all the service was free. With kind permission from the Graduate School, I was able to divert my funding to accommodation and expenses. This meant that I could stay overnight in Edinburgh and spent three whole days in the archive, during which I managed to process the collection in its entirety. Being able to do this will give my PhD greater depth and nuance. Thank you, HES, thank you, Manchester Met.