I am a firm believer that the best research comes from both a professional and a personal investment in the material. The journey of my PhD is one that began in childhood. I turned to the media, as so many young people do, to make sense of my own identity. Growing up in the 90s and early 2000s, the spectre of Section 28 still loomed over my schooling, and the only reason I had heard the word “bisexual” was because I had been raised on the music of David Bowie. The first connection I felt with a fictional character was Buffy the Vampire Slayer’s iconic, history-making queer witch Willow Rosenberg. This was also where my infatuation with the Gothic began.

My thesis, entitled ‘Depraved’ Bisexuals: Biphobia and Bisexual Erasure in Contemporary Supernatural Television, is in many ways a chronicling of my own journey as a bisexual woman through the media of my youth to the present day. With Buffy and its spin-off Angel as my starting point, I chart representations of bisexuality throughout Gothic TV in broadcast, cable and streaming television in the US. Despite being British, my adolescence was dominated by US-created television, and Hollywood’s global dominance has shaped social attitudes throughout the world. My decision to focus on the Gothic, and specifically supernatural Gothic, is in part a reflection of my own history of discovery. As I aged, and the internet gave me the opportunity to understand what bisexuality meant, I found myself returning time and again to supernatural Gothic texts and identifying with those complex, misunderstood monsters of programmes such as True Blood and the homoerotic (if queerbaiting) adventures of the Winchester brothers and the angel Castiel in Supernatural. I discovered that my alternating feelings of pride and shame mirrored how explicitly or implicitly queer characters were presented in these programmes. As social media grew, and fandom moved online, I discovered I was not alone.

In his influential book Monsters in the Closet: Homosexuality and the Horror Film, Harry M. Benshoff chronicles the queer-coding of monsters, creatures and villains through the history of horror cinema. Focusing specifically on gay men, Benshoff’s research acknowledges that many of these texts, such as James Whale’s Frankenstein (1931), came from queer creators. Thus, while their monstrosity was acceptable to a homophobic mainstream market (with many of the texts examined created prior to the Stonewall Riots and gay liberation movements), gay viewers could connect with the feelings of otherness. Before the trend of sympathetic monsters that gave mainstream audiences Barnabas Collins, Angel and Edward Cullen, the creatures of horror cinema were becoming queer icons.

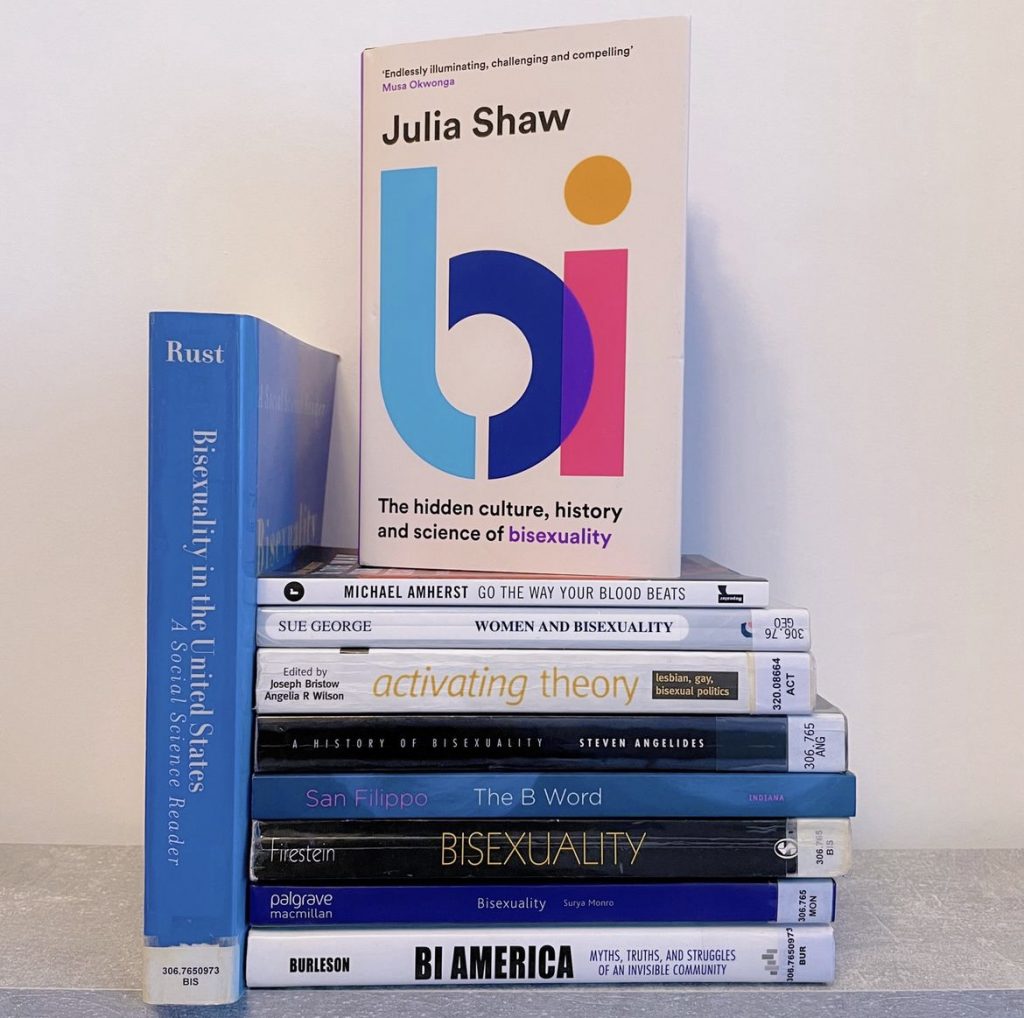

As I began to consider this through my prior Masters research, I discovered a dearth of research specifically referring to bisexuality. In the rare cases where bisexuality was mentioned, it was often an afterthought, lumped in with gay and lesbian identities, with some researchers continuing to deny its existence. I found this curious given the distinct challenges facing the bisexual community with regard to negative stereotypes and a strong monosexual culture. Bisexuality was often presented as a liminal phase: an identity one claimed when in denial about being gay, a period of experimentation, a ratings-grabbing same-sex kiss during sweeps week. Concurrently, I was noticing a growing trend of bisexual characters appearing in supernatural television, from the bombastic omnisexuality of Captain Jack Harkness in Torchwood to the recent adaptation of Interview With the Vampire daring to go where the 1994 film could not, and the comedic insatiable lust of Laszlo Cravensworth in What We Do in the Shadows. Bisexuals appeared as vampires in True Blood, werewolves in Teen Wolf, witches in The Chilling Adventures of Sabrina and cannibals in Hannibal, amongst others. Once again, I related to these characters, now often heroes as well as villains, humans and creatures alike. The gap in the research needed addressing, and thus my thesis began.

The most satisfactory part of my research has been learning more about the LGBTQ+ community and my place within it. My research has called for me not only to discover more about bisexuality, but to look into other, less frequently acknowledged identities such as pansexuality and asexuality. I have challenged preconceived notions I held because of the media I consumed about kink communities such as BDSM. It is through researching these supernatural figures that I have come to understand my own place in the LGBTQ+ community, and find my own pride.