I began my PhD in the midst of the pandemic. The world came to a halt, as though a foot had come down hard on the brake pedal of life, enforcing a global emergency stop. I was a mid-career professional musician with an international reputation as a music educator. As the pandemic took over, my return to the UK from China, (where I was working at the time), gave me an opportunity to stop and think about the critical questions I wanted to ask about my profession, to spend time reading, talking to colleagues and understanding music education from different perspectives.

Undertaking a PhD has been an (almost) life-long ambition. For many years, I knew that research into music pedagogy, and specifically instrumental teaching was going to be my broad area of focus, though it was not until I began completing the requirements for the Fellowship of the Higher Education Academy (FHEA) that my research ideas started to take shape. In preparation for this qualification, my own teaching practice was observed and critiqued, and likewise, I observed others teach and critically reflected upon their work. It was during this process that I began asking questions about how instrumental teachers in conservatoires engage with their students in collaborative ways, not only to enhance their learning experiences, but to support students in growing to become autonomous musicians.

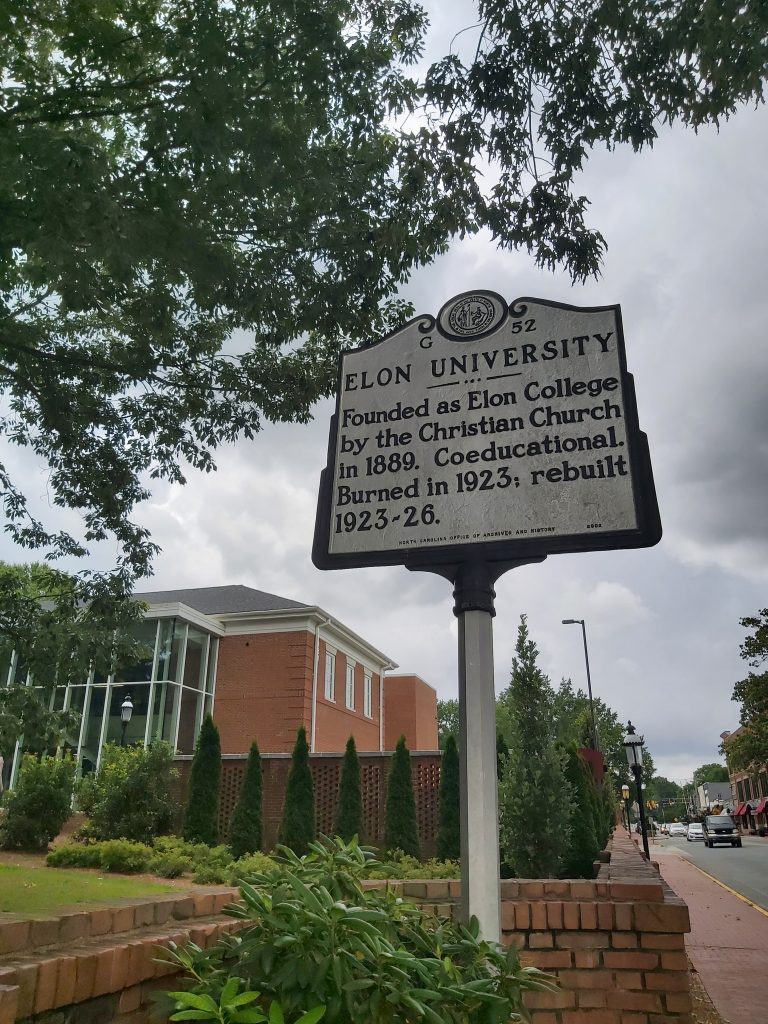

I delved into the literature surrounding conservatoire education, not only in the UK but internationally. I also explored existing research about co-creation of curriculum and engaging students as partners in higher education. I began to question the meanings which are ascribed to student voice, power relationships in education and what happens in the spaces between what is taught and what is learnt. I was drawn to the work of higher education establishments that had implemented student-teacher partnership programmes in their institutions and had developed opportunities for teachers and students to work together in collaboration; for example, the Centre for Engaged Learning at Elon University in North Carolina, and the SaLT programme (students as learners and teachers) at Bryn Mawr and Haverford Colleges in Pennsylvania. Through my explorations, I discovered that a global research network in what is known as SaP (Students as Partners) and SoTL (Scholarship of Teaching and Learning) was thriving in a number of institutions around the world.

I had to negotiate a starting point for my research, and as a classically trained conservatoire pianist with extensive experience, both in specialist music teaching and in higher education, I began by looking at conservatoire piano teaching. I wanted to better understand conservatoire piano student’s lived experiences of being engaged as partners in their instrumental learning and what partnership meant for them. Likewise with professors, I wanted to know about how they described and facilitated partnership in their practices. I completed two interview studies with professors and students using the methodological approach of Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis.

As I was coming to the end of collecting my interview data, the ‘call’ for presentations was announced by the Centre for Engaged Learning at Elon University for their International Conference. I saw an opportunity to connect with the community of practitioners I had been reading and writing about for the last three years, and moreover an opportunity to share my work in progress with experts from the SaP and SoTL communities. After peer-review of my submission, I was delighted to find out that I had been invited to present at the conference and began my plans to travel to North Carolina.

My presentation on ‘Engaging Students as Partners in a Music Conservatoire’ was very well received, but the most poignant take-aways from the conference were listening to and engaging with the work of other SaP practitioners from around the world. Especially illuminating was a practical workshop on feedback literacy in higher education which gave me lots to think about in terms of how feedback is given and received in conservatoire teaching, and the mechanisms by which feedback is generated. Likewise, a group presentation on a research project examining trust in pedagogical partnership was inspirational, particularly as trust is a vital part of effective practices in instrumental teaching, as well as an emerging theme from my research. I had the honour of talking extensively to Peter Felten, who with Cathy Bovill and Alison Cook-Sather wrote the seminal book on ‘Engaging Students as Partners in Teaching and Learning’ (2014). This is the first book I read on SaP practices and has stayed with me all the way through my PhD research. Talking to Peter and his colleagues about the intersections between our work was an unforgettable privilege. Further meaningful discussions and sharing of ideas with academics from Australia, New Zealand, Singapore, Europe and the USA have led to communications since the conference, with potential to explore future collaborations.

I arrived at Elon the day before their conference and orientated myself with their beautiful, leafy campus; I was in awe – here was the home of the community of practitioners whom had provided inspiration for my PhD research, and here I found myself standing on their soil. What I found at Elon, in the strongest sense of the word, was COMMUNITY. A community of inter-disciplinary professionals working with common goals to facilitate collaborative, democratic and relatable educational experiences for their students – a place where fostering an ethos of inclusion, and where student and teacher expertise interacts, is at the forefront of all endeavours.

I would like to thank Manchester Metropolitan University, the Royal Northern College of Music and Elon University for their financial support in enabling me to undertake this trip. Likewise, thanks are due to my supervisors Dr Jennie Henley and Dr John Habron-James at the RNCM, and Dr Ben Wild at Manchester Met.