In celebration of National Fitness Day, Nathan, one of our PhD researchers, has written a blog about the importance of physical activity, and in relation to his research area of developing an exercise intervention that reduces the bone and muscle function deterioration of women experiencing the menopause transition.

The adage of “it’s never too late to start. The best time to start was yesterday, but the next best time is today”, holds particularly true for the impact which physical activity can have on our health, affording a lower risk of developing numerous diseases and conditions that are most common in the UK (eg, cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, depression, cancers, osteoporosis and dementia). For this blog, physical activity refers to any activity that provides an energy expenditure above what is expended while sitting (ie, walking, using stairs, household chores etc), while exercise is just physical activity performed in a planned, structured manner (ie, going for a run, sports training, going to the gym etc).

The UK Chief Medical Officer’s physical activity guidelines recommend adults (18+ years old) to achieve 150 minutes/week of moderate intensity activity, or 75 minutes/week of vigorous intensity activity, or a combination of both. Moderate intensity physical activity increases your breathing rate, to where you are still able to talk but not sing and includes activities such as brisk walking, dancing, general gardening or household chores, or a moderately challenging cycle/swim. Vigorous intensity physical activity causes a fast-breathing rate, to where it may be difficult to maintain a conversation and some examples include climbing stairs, heavy gardening (eg, digging, cutting trees), jumping rope or intense jogging/cycling/swimming).

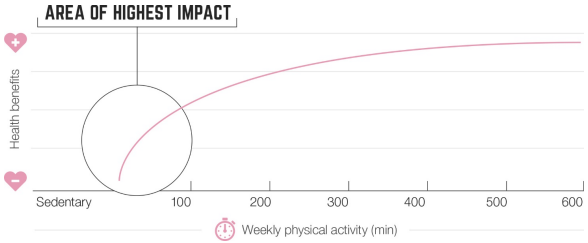

While although these are the time thresholds set for the guidelines, these are by no means the thresholds at which the health benefits begin for exercising.

If you feel like these physical activity targets are far beyond your current physical fitness ability level, it is important to note that the greatest benefits for increasing your activity level are received by those who are least physically active (see image below). ‘Exercise snacking’, the idea of accumulating multiple short periods of activity (ie, 1-5 minutes at a time) over the course of a day may be a more feasible approach for those who are less physically active, or even for students and office workers to break up long periods of sitting. Aside from exercise snacking, additional small changes that could be made to make everyday living more physically stimulating include:

- Increasing the frequency that you use the stairs each week (even if this only means you get the elevator from the floor below or above).

- Increasing the activity of your commute (eg, get off the bus a stop or two early, park your car further away from work/university or cycle some portion of the distance etc).

Central to the new physical activity guidelines is the recommendation for muscle strengthening activities to be performed twice weekly. Although traditionally this would be thought of as doing heavy weights training, there has been a shift in focus as to how we can incorporate muscle strengthening activities into everyday life without the time and cost requirements of joining a gym (eg, carrying shopping bags/baskets, gardening, intensive household chores etc). Maintaining strength is crucial for reducing our fall and fracture risk as we age, as well as to preserve our ability to carry out daily tasks. Although you may be thinking “it’s ok, I’m only in my 20s, I don’t need to worry about my health in my 60s and 70s yet”, our bone and muscle function begins to decrease from our 20s and 30s, respectively. Unfortunately, this rate of decline accelerates from the late 40s onwards, particularly so for women reaching menopausal age (typically 45-55 years old).

My research at Manchester Met will focus on developing an exercise intervention that reduces the bone and muscle function deterioration of women experiencing the menopause transition. Bone tissue is constantly going through repeated cycles of breaking down old and damaged bone tissue and forming new bone to replace it. The hormonal changes experienced around the menopause cause the rate of bone to breakdown to exceed the rate of replacement. In the 4-5 years following the final menstrual period (the onset of the postmenopausal phase), the level of bone loss per year for postmenopausal women can be as high as 50-200% greater than a man or woman of similar age (who has not yet experienced menopause). Resultingly, there is a large discrepancy in the UK lifetime risk of suffering a bone fracture after the age of 50 (due to having low bone mass), for women (1 in 2) when compared to men (1 in 5).

While previous exercise programmes in this general area have been effective, very little research has been done on the effect of exercise in women currently experiencing the menopause transition. Exercise is preferred to bone medication treatment in a menopausal population due to the added benefit of improvements in muscle strength and fall risk, which are not affected by bone medication. Many people will be familiar with the common reasons for not exercising as much as we would like to, including “I haven’t got the time”, “I don’t have access to suitable facilities” or “I’m afraid I may get injured or don’t feel physically capable”. We hope to develop an exercise programme for a menopausal population that is safe, enjoyable, and effective at catering to the unique muscle and bone needs of the population.

When thinking of exercise for bone health, the activity should incorporate as many of the following as possible: 1) involve movement, 2) be weight-bearing, 3) involve multidirectional movement, 4) provide greater impact on the bones that your usual walking pace, or 5) be an activity that involves movement not usually performed during everyday living. Bone does not require large amounts of exercise to receive improvements. As little as 6-10 repetitions or impacts at a time for 2-4 sets can be effective at increasing bone mass. Some examples of activities beneficial for bone are included below:

| Low-moderate physical capability | High physical capability |

| – Bodyweight exercises (eg, squats, lunges, sideways lunges, shoulder press etc) | – Weight training exercises (eg, squats, deadlift) |

| – Stairs climbing | – Fast stairs climbing |

| – Walking backwards or sideways | – Jogging backwards and sideways shuffles |

| – Recreational sport (eg, 5 aside football, basketball, badminton, volleyball etc) | – Recreational or competitive multidirectional sport |

| – Dancing | – Dancing |

| – Low intensity forward, sideways, or backwards hops | – Moderate to high intensity multidirectional jumps or jump rope |

| – Short bouts of low intensity jogging or running | – Short bouts of sprinting or high intensity running |

Key takeaways:

- Do what physical activity you can, no matter how little, and strive to increase this over time.

- Don’t neglect the importance of increasing and maintaining muscular strength.

- Although your muscle and bone function decrease with age, remaining physically active as we age is effective at offsetting the decline that would otherwise occur.

- Exercise, performed safely, does not increase the risk of bone injury when we get older. Instead, it makes bones more resilient to breaking and reduces our risk of falling.

Useful resources for further information:

- UK Chief Medical Officer’s Physical Activity Guidelines

- The effect of physical activity for reducing the risk of mortality

- Daily step count and risk of developing cancer or cardiovascular disease

- The importance of muscle strength for reducing the risk of chronic disease – https://www.bmj.com/content/361/bmj.k1651 & https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00125-019-4867-4