As it is Movember, an annual event involving the growing of moustaches during the month of November to raise awareness of men’s health issues, such as prostate cancer, testicular cancer, and male suicide, I would like to take this opportunity to share some of my PhD research. My understandings of prostate and testicular cancer is not another guide on how to “beat” or “conquer” cancer, full of dubious alternative therapies. I am not a doctor and I have no interest in offering unqualified medical advice.

My thesis kick-started from essentially the experiences of my father-in-law which I witnessed first-hand, written with as much vividness and candour as I could muster, through his travails of cancer treatment, his brain fog of chemo, the fatigue of hormone therapy, and the lingering existential dread of an advanced and incurable cancer diagnosis. Watching my father-in-law, an alpha male who had not taken a single day off all his working life succumb to this dreadful illness, prostate cancer, was a tragedy.

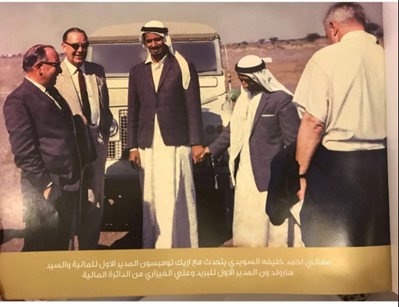

My father-in-law belonged to what was one of the first cohorts of students to leave behind the harsh climate of Abu Dhabi in the Arabian peninsula as a young 18-year-old man for the fresh pastures of Cambridge University. Armed with his master’s degree in finance, he eventually returned home to establish the Ministry of Finance in Abu Dhabi where he worked from 1960 to 1996, established Al Wahda Football Club and also took the responsibilities of the chair of Corniche Hospital, Abu Dhabi and Alain Housing Authority over 60 years ago.

It was an absolute joy to sit and listen for hours on end to his adventures around the world including those to Hawaii, Honolulu, Japan and East Asia. He would tell us stories of when he’d ordered a fish at a restaurant and they brought it alive and flapping its tail to the table. He was full of joy when talking of the English, praised the beautiful English accent and always told his sons to learn English from the English and not anywhere else, which led to my husband venturing off to study in the UK where we first met.

When we received news of his dreadful diagnosis, time stood still and everything turned dark. I closed my eyes and shuddered at the thought that his round the world adventures would become a round the world treatment trip. This man who I would see every day and who I had grown so very attached to maintained his beautiful camaraderie and hope as he travelled with his sons to Thailand, India and Cleveland, Ohio in pursuit of treatment but sadly succumbed to his ailment in 2022 at the grand age of 84 years.

I began keeping a diary, purely as a personal coping strategy, writing therapy, to try and help me process the many stressors and uncertainties of this experience. As time went on, I began to suspect that something could have been done to save men like my father-in-law. Why hadn’t he had his prostate checked before? Would he have gone to get checked if an opportunity presented itself? How can we encourage stubborn men to take digital rectal exams when prostate cancer is symptomless? How can we reach out to men and educate them on this silent killer? If men were aware that just because they had no symptoms did not mean they may not have cancer, more men might take up offers for tests. This could mean more tumours are identified at an earlier stage and reduce the numbers of men experiencing late presentation with incurable disease. I set out with a personal mission that I would like to see a more integrative approach to cancer care, treating the whole person and not just the tumour, affording patients a greater sense of dignity, agency and empowerment in how they navigate their path through cancer treatment.

Background

The prostate, a small gland located near a man’s bladder with a role in semen production, has been described both as ‘the breast that got lost’ (Kedrowski and Sarow, 2007: 135) and ‘the problematic third testicle’ (Oliffe, 2009: 33). Like the breast and the testicle, the prostate is not just a biological component situated within the body; instead, it is embodied in a cultural, social and medical setting. The cancer associated with the prostate, prostate cancer, is the most common cancer in men in the UK (Cancer Research UK, 2022), making it the focal point of extensive clinical research. The growing interest in research and policy has led to the development of a range of clinical guidance for the detection, treatment and management of prostate cancer.

My thesis explored qualitatively how asymptomatic (producing or showing no symptoms) men, and women, understand prostate and testicular cancer and how they would manage a hypothetical diagnosis of these cancers.

The Findings

Thematic analysis of my studies found many key themes. One of the dominant themes was misconceptions and misinformation about the prostate and prostate cancer where it was found that misinformation about the prostate, its location and its function was rife. Participants often showed confusion with regards to the medical terminology surrounding prostate cancer, confused terms such as impotence and urinary incontinence, and some were unaware that the prostate was exclusively a male organ.

Many men had no knowledge regarding the aetiology of prostate cancer. Poor levels of knowledge were shown by many of the men when discussing the causes and risk factors for prostate cancer. One example of misinformation of the risk factors for prostate cancer was the disease being caused by poor hygiene, not using a condom and having sexual relations out of marriage. The idea that men can contract cancer from women as a result of women’s poor health appeared.

Further myths surrounding prostate cancer included the risk of developing the disease if a man had not been circumcised or had too many partners, which is untrue as prostate cancer can happen to anyone whether they are circumcised or not. In terms of sexual activities and dangers, some men believed that receiving forceful anal penetration and being in a homosexual relationship as a receiving partner raises the risk of prostate cancer, which is untrue.

Confusion with medical terms and terms surrounding prostate cancer were common amongst the men. Some confused bowel function with urinary function, and often referred to bowel habits as incontinence. Others referred to the prostate incorrectly as the “prostrate” throughout their interviews. One even used the term “viral load” when discussing prostate cancer in a similar way to how one would refer to human immunodeficiency virus in the blood as an example and not to prostate cancer.

The lack of knowledge about the prostate exam and its effects was evident in many of the interviews. Misunderstandings regarding the methods of testing for prostate cancer were rife amongst the men. One of the widespread misconceptions was that cancer is only prevalent in men if there were symptoms of the disease when actually many men with prostate cancer display no symptoms until the cancer is quite advanced. Some men incorrectly understood that the testing procedure for prostate cancer is a swab in the rectum. Others assumed that the colonoscopy exam was simultaneously a prostate exam. The confusion seemed to stem from the fact that screening methods for each involve an evaluation through the anus. Whilst colonoscopies do use a flexible camera with the goal of detecting polyps in the colon, prostate examinations do not involve the use of a camera. Instead, a gloved finger is used to gently feel the prostate (Prostate Cancer UK, 2022). Some believed that prostate cancer could spread through the biopsy exam and that the exam is linked with impotence. Producing a semen sample as part of the prostate exam was another myth that put some off going to undertake the screening exam.

On the whole, interviews were riddled with misinformation and misconceptions and the view – that“ you shouldn’t worry about prostate cancer if there’s no symptoms” was prevalent, although many men with prostate cancer display no symptoms until the cancer is quite advanced.

This study established that men’s awareness and knowledge about prostate cancer is very low and marred with misconceptions. Informal sources of communication, particularly friends, continue to be the main sources of information about prostate cancer, while formal sources are passive. The aforementioned findings imply that policy makers in health delivery programmes have an overdue responsibility to rescue men from the catastrophic trap so that they freely enjoy their rights to good health. There is also a need for advanced information, education and communication regarding male reproductive cancers to cater for the future welfare of men given that they are drivers of national economies in their various capacities. Failure to do so would mean that men’s reproductive health-seeking behaviour regarding early screening and treatment of prostate cancer will forever remain compromised.

An urgent need to renew the message

The majority of participants in this study had a false sense of security that if they did not have any urinary symptoms, then they would not need to test for prostate cancer. There is now a strong need to emphasise that prostate cancer is silent or asymptomatic, particularly in the curable stages. Waiting or looking out for urinary symptoms might potentially give a false sense of reassurance that all is well and delay presentation when the disease is treatable. Nevertheless, we are not advocating that men with urinary symptoms be discouraged from presenting for investigation but rather that it should be recognised that male urinary symptoms cannot be used as a cardinal indicator of prostate cancer.

Conclusion

The public messaging suggesting that prostate cancer directly causes urinary symptoms must be reviewed. To maintain this fallacy is misleading. Efforts should instead be made to raise awareness that prostate cancer does not manifest with urinary symptoms and can be silent. I therefore call on health bodies, charities and the media to take urgent action to review the current public messaging and referral recommendations.

References

- Cancer Research UK (2022) Prostate cancer incidence statistics. Available at: https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/health-professional/cancer-statistics/statistics-by-cancer-type/prostate-cancer#heading-Zero [Accessed 12th May 2022]

- Kedrowski, K. & Sarow, M. (2007) Cancer activism: gender, media and public policy, University of Illinois Press

- Oliffe, J. (2009) Positioning prostate cancer as the problematic third testicle. In Broom, A. & Tovey, P. (Eds.) Men’s health: body, identity and social context. United Kingdom, Wiley-Blackwell Publications. 2, 33-62

- Prostate Cancer UK (2022) Prostate Information. Available at: http://prostatecanceruk.org/ [Accessed 5 November, 2023].