To mark International Women’s Day on Friday 8 March and the 2024 theme of ‘Inspiring Inclusion’, Amal Mazouz shares reflections from her doctoral research, focusing on Muslim women’s representation and breaking stereotypes.

My research focuses on the representation of Muslim women in contemporary western non-fiction. In other words, should a Western woman, say of English, American or French nationality decide to live in a Muslim country and write a book about it, be it a memoir or a travelogue, my task is to analyse how she represents the Muslim women in this country.

My research is based on Edward Said’s seminal work Orientalism (1978), in which he defines the latter as a discourse, or a body of knowledge produced by experts who have institutional prestige. I also use the work of other scholars – feminists mainly who built on Said’s work – and moved away from it to focus on the role of Western women in imperialism and the production of Orientalist knowledge. This includes feminists like Reina Lewis who wrote Gendering Orientalism (1996) and Rethinking Orientalism (2004), Sara Mills who wrote Discourses of Difference: An Analysis of Women’s Travel Writing and Colonialism (1991) and Mary Louise Pratt who wrote Imperial Eyes: Travel Writing and Transculturation (1992). When researching postcolonialism, one naturally cannot forget Gayatri Spivak and her ground breaking essay ‘Can the Subaltern Speak?’ (1988), as well as Homi Bhabha and his ‘Of Mimicry and Man: The Ambivalence of Colonial Discourse’ (1984). Contemporary scholarly work based on Said’s work includes Lila Abu-Lughod’s Do Muslim Women Need Saving? (2015), which is an equally important text in my theoretical framework.

I chose for my research subjects Western female authors from both the United States and Europe, and who lived in different Muslim countries, lending my project a wider and a more diverse scope. I chose American authors Jean Sasson and Willow G. Wilson, who lived in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and Egypt respectively, French author Anna Erelle who travelled virtually to Syria, and British author Christina Lamb who co-authored I Am Malala (2013) with Malala Yousafzai. My chapters move from viewing the Orient from the perspective of a Western woman, as Sasson does in her Princess series, to being in the skin of a Muslim woman, as Erelle does when she pretends to be ‘Mélodie’, a Muslim woman in her Undercover Jihadi Bride (2015), to actually embracing Islam as Wilson did, representing the voice of both a Muslim and Western woman in her the Butterfly Mosque (2010). My last chapter was meant to represent purely the voice of a Muslim woman – Malala – however, after analysis I concluded that I Am Malala (2013) is a mixture of voices, of which Malala’s is barely noticeable.

Breaking the negative stereotypes:

I chose to do this research project for two reasons. First, I have grown tired of seeing the negative representation of Muslim women on social media and news outlets, and recently in literature as well. What is more, I have grown tired of Muslim women being used as an excuse to invade or interfere in Muslim countries. Spivak’s ‘White man saving brown women from brown men’ is crystallised in Laura Bush’s address to the nation in 2001, in the aftermath of the 9/11 events. ‘Saving’ Afghan women was at the top of the priorities list when the U.S invaded Afghanistan, as Mrs Bush declared: ‘Because of our recent military gains, in much of Afghanistan women are no longer imprisoned in their homes. They can listen to music and teach their daughters without fear of punishment.’ 1 This same justification was used during the U.S invasion of Iraq, with the slight difference of replacing the Taliban with Saddam Hussein who was equally demonised. During the Obama administration, the U.S continued to interfere in the area by authorising drone strikes in Pakistan in the same counter-terrorism scheme, and for the purpose of ‘saving’ the locals, including women. Malala Yousafzai is one of the ‘victims’ who was ‘saved’ figuratively and literally by being flown to Birmingham after her head injury in 2012.

Secondly, I have realised the value that the word ‘non-fiction’ adds to a book description, creating the illusion of authenticity and transparency, while in fact all that matters is the sales of a book rather than its ‘truth’. Furthermore, living in a Muslim country seems to give these female Western authors credibility, indirectly influencing the public opinion regarding issues related to Muslim women. An example is Erelle writing ‘I felt like I was suffocating inside my thick black veil. Frustrated, I took it off, drank a large glass of water, and lit a cigarette.’ 2 Here, the Western reader is led to understand that the veil is oppressive to women, because Erelle has experienced it first-hand, and she says so. This is akin to Hoodies’ ‘Freedom is basic’ advert, which shows a model ripping off her veil then enjoying ‘freedom’. Both Erelle and Hoodies are creating a negative stereotypical image of the veiled Muslim woman. Another example is when Wilson admits: ‘I still believed this, however unconsciously, the idea that Omar might expect me to do nothing but cook and scrub floors filled me with terrifying images of domestic slavery.’ 3 Here, Wilson is promoting a negative image of an Egyptian Muslim woman as a slave whose mission in life is to cook and clean for her husband. My last example will have to be Sasson’s dedication of the last Princess sequel, Princess: Stepping out of the Shadows (2018):

‘To the girls and women of Saudi Arabia who have suffered and died under the archaic guardianship laws of our country, we will remember you.

And those suffering still, help is on the way.’ 4

Sasson, using Sultana’s voice, portrays a negative image of Saudi Muslim woman as shackled by the guardianship laws that Sasson describes as `archaic’ and `outdated’, and ends her dedication with a promise of ‘rescue’.

All the above stereotypes are negative, victimising the Muslim woman, and portraying her as ‘oppressed’, ‘silenced’, ‘segregated’, ‘subservient’, and ‘slave’.

Never judge a book by its cover:

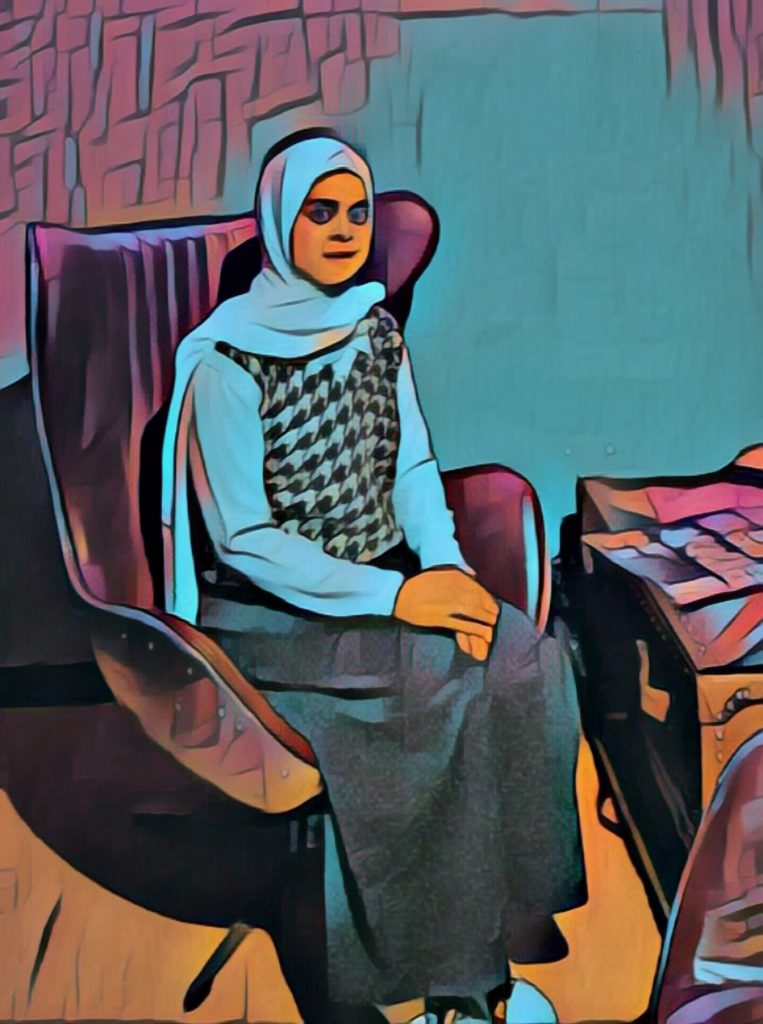

This year, for International Women’s Day, instead of asking you to do something, I ask you not to do something. I ask you not to believe everything you read just because it is labelled as non-fiction, or because it is headed with a disclaimer that says a ‘true story’. I invite you all to ‘search’ for ‘truth’; after all, it is our duty and burden as researchers. And so it is my duty to share my ‘truth’, that when I first started this PhD project, I naively thought I was going to change the world! I thought I could change how the world views Muslim women, but now I settle for telling you how proud I am of being a Muslim woman. I am not oppressed or silenced, I am a proud doctoral student from Manchester Metropolitan University, and this is my voice, and my ‘truth’.

References:

1. Anna Erelle, Undercover Jihadi Bride: Inside Islamic State’s Recruitment Networks. trans. Erin Potter (Harper Collins, 2015).

2. ‘Radio Address by Laura Bush to the Nation’, in US Department of State Archive (Online: 2001).

3. Jean Sasson, Princess: Stepping out of the Shadows (2018).

4. Willow Wilson, The Butterfly Mosque: A Young Woman’s Journey to Love and Islam (2010).